Kyoto Fusioneering looks toward a ‘Made in Japan’ approach for nuclear fusion

Ever since the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California achieved ignition in a nuclear fusion experiment in December 2022, a new wave of excitement and hype has grown around the energy source, which has long been tipped to help usher in an era of abundant, clean and safe energy.

That breakthrough in the U.S. has been followed by several more, including some earlier this year. Britain’s JET laboratory, for example, in February produced a record amount of energy through nuclear fusion, which sees atoms smashed together so that they combine and create energy due to their relative weights — the opposite process of conventional nuclear power.

Nuclear fusion is also enjoying high-level political support. In April, the Group of Seven’s energy and environment ministers meeting threw its backing behind the energy source, promising to promote collaboration, establish a working group on the topic and work to develop consistent regulations within the G7.

“It has the potential to provide a lasting solution to the global challenges of climate change and energy security in the future,” the ministers said in a statement. “The successful delivery of fusion energy production could offer major social, environmental, and economic benefits.”

Harnessing fusion, the process that powers the sun and stars, has long been dogged by slow, incremental progress — to the point that there is a recurring joke that the technology is always 30 years away. But against this backdrop and growing moves toward commercialization, startups in the space are targeting much more aggressive timelines, with many saying a fusion plant will deliver power to the grid as early as between 2031 and 2035.

Still, numerous issues remain unsolved, although the nature of them has arguably changed.

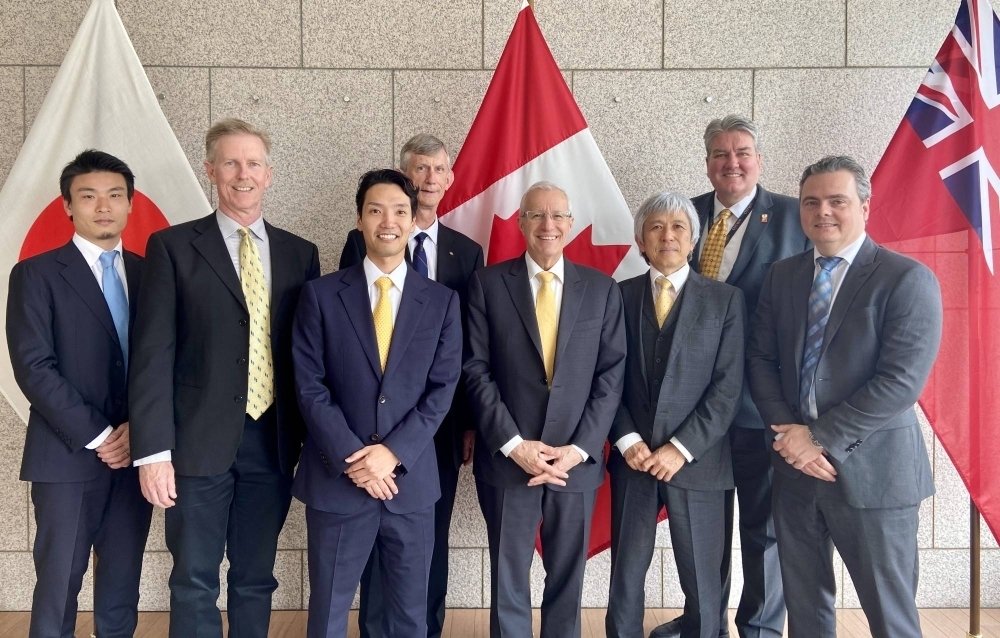

For Kiyoshi Seko, director and chief operating officer at startup Kyoto Fusioneering, a key component of this large-scale shift around nuclear fusion is the move from scientific challenges to those related to engineering.

“Now we are in the … engineering challenge phase. How to solve those engineering challenges, that’s our bottleneck,” Seko says, citing the need for certain components to handle temperatures as high as 1,000 degrees Celsius.

1 comment